The story of the newest Panthers head coach doesn’t start in Carolina – it starts in New York. By the time the 2019 season drew to a close, it was obvious that the New York Giants needed to go back to the drawing board at head coach. And examining NFL head coaching prospects on the market, there seemed to be the perfect candidate to bring the Giants back to their old, winning ways.

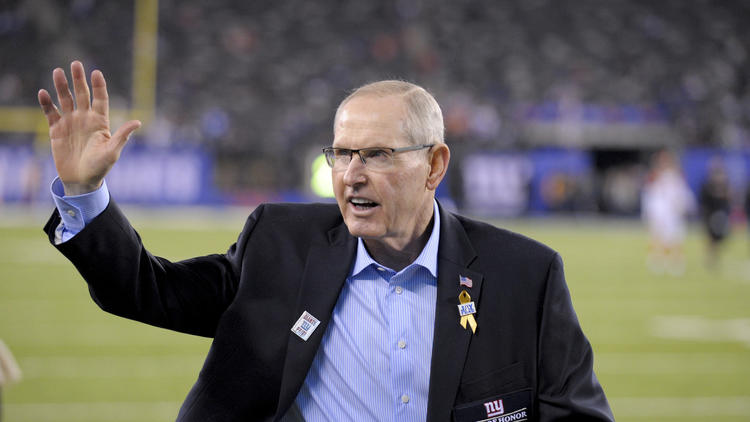

In 2012, just one year after their triumph in Super Bowl XLVI, the Giants’ coaching staff under franchise great head coach Tom Coughlin featured an assistant offensive line coach by the name of Matt Rhule. A little-known coach in his first NFL job at the time, Rhule’s year on Coughlin’s Giants would lead him directly to his first head coaching opportunity at Temple University. And by the end of 2019, Rhule had become a hot candidate for an NFL head coaching job – heralded as the “savior” of a Giants franchise that had lost its way post-Coughlin.

For weeks on end, the New York tabloids built up Rhule, a native New Yorker and Coughlin accolite, as the “prohibitive favorite” to restore Big Blue to its former glory. And the Giants themselves were eager to bring the familiar face of Rhule back into the building. When Rhule’s interview for the Giants’ head coaching job was set for January 7, the red carpet of coronation was formally laid out: To plenty, Rhule becoming the “true successor” to Tom Coughlin as Giants head coach seemed like a given.

Only, Rhule didn’t take the Giants job – he never so much as made it to the building.

Instead, he signed a long-term and lucrative deal to become the next head coach of the Carolina Panthers.

After receiving a seven-year, $60 million offer from the Panthers – one the Giants, blown away by head coaching interview and eventual hire Joe Judge, were not willing to match – Rhule settled on making Carolina his first NFL head coaching job. But entering his first season with the Panthers, Coughlin – a two-time Super Bowl Champion and one of the NFL’s top coaches of the last quarter-century – has nonetheless remained a major influence on Rhule.

In Rhule’s first months in Carolina, he sought Coughlin’s counsel in adjusting from the college level back to the NFL. And in multiple past interviews, Rhule has spoken glowingly of Coughlin and his time on his staff as a major influence on his coaching career.

“As I went to be head coach at Temple [in 2013], I tried to apply all the things that I had learned from Tom,” said Rhule on a recent RapSheet & Friends podcast. “I thought Coach Coughlin was amazing at his ability to get his message across to the entire team by visiting with one guy at a time. We had some personalities, some great players on that team: [Jason Pierre-Paul], Justin Tuck, Eli Manning, Ahmad Bradshaw.”

“I thought Tom did a great job of going to those guys and understanding that they were probably influencers on the team and making sure the message was getting out there.”

Coughlin’s example offers plenty of lessons for Rhule, as both followed similar paths to their first NFL head coaching jobs: Coughlin was a wide receivers coach on Bill Parcells’ Giants staff, then went to the college level as the head coach at Boston College and parlayed that into his first NFL head coaching job with the expansion Jacksonville Jaguars. And many of the teaching points that made Coughlin a championship-winning head coach were laid out in his book, Earn The Right To Win: How Success in Any Field Starts with Superior Preparation.

Published after the Giants’ Super Bowl XLVI win, Coughlin’s book outlined much of his coaching philosophy, which is at its basis: “create an environment and provide the direction necessary to allow our players to perform to the best of their ability, which will lead directly to success.” In two decades as an NFL head coach, Coughlin’s philosophy and methods alike were highly effective even as his reputation soured over the past few years after the NFLPA challenged Coughlin over exorbitant fines and disciplinary measures he enacted, dating back to 2018, in Jacksonville which ultimately led to his firing. His Jaguars teams (1995 – 2002) went to two AFC Championships in the franchise’s first five years, while his Giants teams (2004 – 2015) persevered against the odds in two remarkable Super Bowl runs, one of which saw them topple the undefeated New England Patriots in Super Bowl XLII.

In examining the accomplishments of Coughlin’s teams and the approach that Coughlin himself took, there is much that Matt Rhule can apply to his current Panthers team, as he seeks to eventually emulate one of his biggest mentors as a Super Bowl Champion.

Build the Structure to Help Re-Instill Pride

Photo Credit: Brad Penner/USA TODAY Sports

Few who have ever served as an NFL head coach know the ins and outs of “building a program” quite like Tom Coughlin. When he arrived in Jacksonville as the first head coach of the Jaguars, he began work at a “facility” which consisted of little more than a single trailer in a muddy field. By their second season in 1996, the Jaguars had managed to win two playoff games and go all the way to the AFC Championship Game – a feat unthinkable for an expansion franchise, and one that hardly occurred by chance or accident.

As an NFL head coach, Tom Coughlin was notorious for his special brand of discipline, with extreme adherence to small details drilled into the minds of his players and staff. The most famous illustration of this, of course, was the practice of “Coughlin Time”: All meetings, practices, and other events under Coughlin’s watch began five minutes early – the clocks on Coughlin’s teams reflected this. If a player showed up to a 9 o’clock team meeting at 8:55, he was right on time. If he showed up at 9 o’clock, he was five minutes late.

As silly and as arbitrary as some of Coughlin’s rules seemed on the surface, they served a very explicit purpose: establish a structure where members of the team knew exactly what was expected of them and the exact level of commitment that would be required from them.

“The structure is a statement: This is who we are, this is what we do, and this is the way we do it. The principles, values, requirements, and demands of the organization are not going to change,” wrote Coughlin. “…If you don’t have a set of rules by which everyone abides, you have chaos, and when you have chaos, there is no structure, and you lose. Whatever rules you make, they have to be stated clearly, so there are no gray areas. Everything needs to be spelled out, with no room for interpretation.

“… Setting tough rules is also a good way of finding out quickly who is committed to the program and who isn’t, who’s going to buy into our philosophy and be willing to pay the price and who wants out, who is in the trenches with us when it gets tough and who isn’t. The purpose of setting rules isn’t to catch people and punish them but rather to find those people who are willing to make a commitment to the team and their teammates.”

Of course, operating on “Coughlin Time” shouldn’t be the direct expectation for Rhule. And in coaching stops at Temple and Baylor, Rhule didn’t go out of his way to mark himself as a disciplinarian. But for any team that has plummeted to the basement of the NFL, raising the standard of what is and isn’t acceptable by raising the standard of discipline is paramount. And just as Coughlin before him, Rhule enters a situation where a once-successful team is now in tatters and wandering directionlessly through pro football purgatory.

When Tom Coughlin returned to the Giants in 2004, 14 years after serving on their last championship team in Super Bowl XXV, he stepped into a building that had lost the luster it once had: After making Super Bowl XXXV and losing to the Baltimore Ravens at the peak of the Jim Fassel era in 2000, the Giants began to tail off significantly, with 7-9 and 4-12 seasons bookending a 2002 season that ended with a devastating playoff loss to the rival San Francisco 49ers. Over that period of time, the Giants lost much of the edge that made them a Super Bowl team and one of the NFL’s blue-chip franchises, with a softer and more complacent mentality resulting in several colossal failures that cost the team big games and ultimately resulted in Fassel’s downfall.

“What we must be about right now, immediately, is the restoration of pride,” said Coughlin in his introductory press conference, “Self-pride, team pride – The restoration of our professionalism and the dignity with which we conduct our business. We must restore belief in the process by which we will win. We must replace despair with hope and return the energy and passion to New York Giants football.”

“The pride in being a New York Giant that had been so much a part of the organization when I had worked for Coach Parcells was missing,” wrote Coughlin. “Everything we did from that first press conference on was intended to restore that pride.”

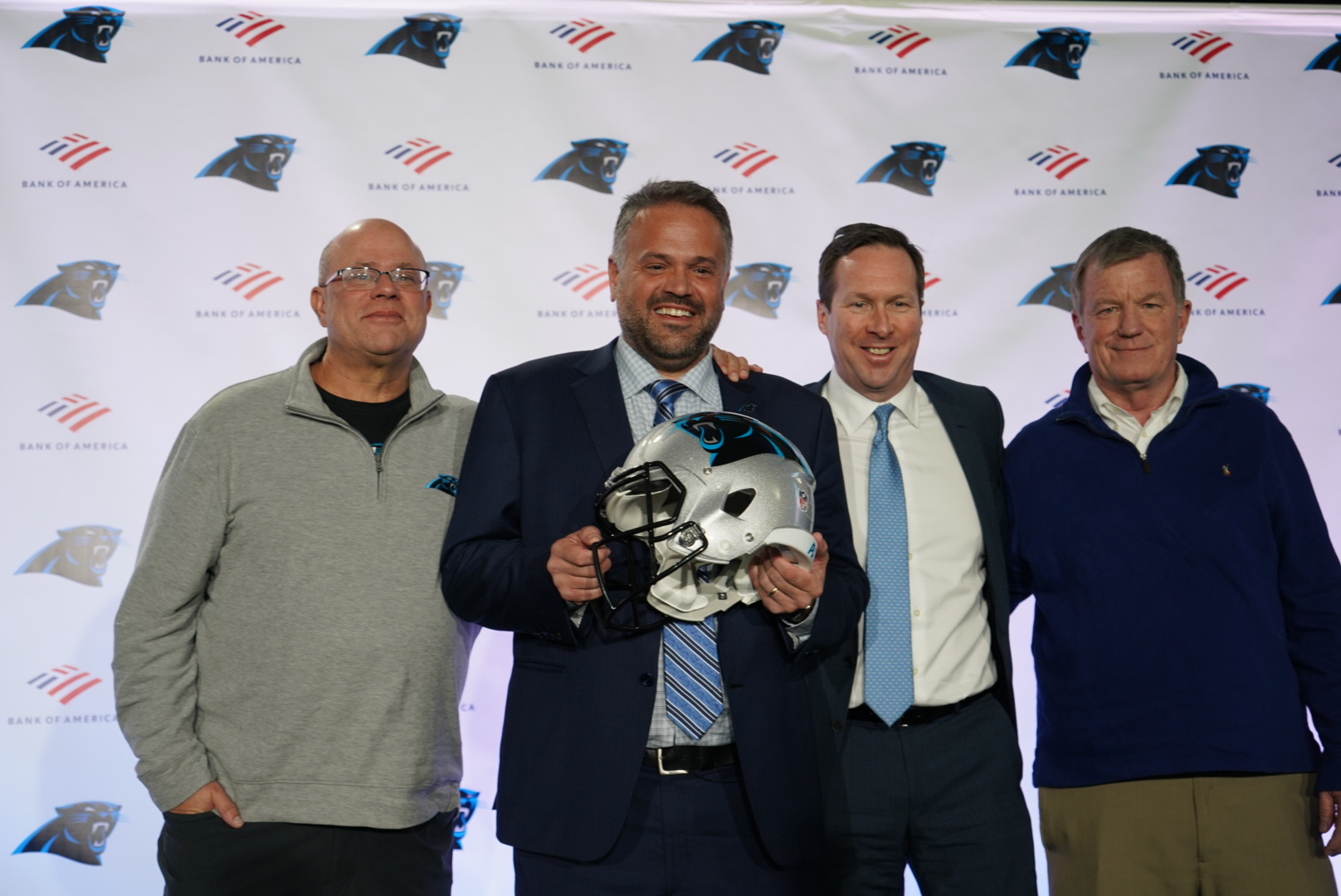

David Tepper, Matt Rhule, Tom Glick, and Marty Hurney

In Rhule’s case, the Panthers are a franchise that has had their pride completely shattered. Once a team that believed they could and would win the game – the Super Bowl – the past two years have seen stretches where Carolina couldn’t seem to win a game. The Panthers have a 7-17 record against their division since Super Bowl 50, and have had to endure the humiliation of losing three times to a division rival in 2017.

When team owner David Tepper made an admonition against the franchise’s “long-term mediocrity” last season, he implicitly spelled out what the Panthers are and what being a Panther stands for: Historically and presently speaking, being a Panther doesn’t mean being a winner.

That considered, the Panthers have had it pretty good for an expansion NFL franchise, particularly since certain long-standing franchises can only wish they could have gone to four NFC Championship Games and two Super Bowls in a quarter-century. But all the successful Panthers teams of the past have featured a pronounced sense of pride: that the Panthers stood for something, were going to do things the way they saw fit, and weren’t going to back down or concede to anyone in their path.

Over the last four seasons, the number of players who felt the pride of the Super Bowl 50 team has dwindled further and further down.

And surely, going 6-18 since the midway point of the 2018 season has taken its toll mentally on the Panthers players who are left, and sullied the image of Carolina Football across the league. In order for Rhule to get the Panthers back to the success they once enjoyed, re-instilling a sense of organizational pride is going to be essential.

And that begins with spelling out the principles of what being a Panther means and setting the standard for what it takes to be one.

Be Firm, But Not Too Rigid

Photo Credit: @TCJayFund on Twitter

Over the past 20 years, there has been a drastic shift in philosophy as to how to properly lead a football team and whip them into shape. Classic militaristic techniques have fallen out of favor, and the previous generation of Panthers actually played a big role in creating a league that celebrates every first down, takeaway, and touchdown – a far cry from the “Stop showboating and get back to the sideline” ways of yesteryear.

Coaching from the 1990s all the way through the 2010s, Coughlin coached throughout the gradual change in the way coaches controlled their players. But even for his time, Coughlin was an exceptionally difficult coach to play for – with his brand of toughness standing in stark contrast to the programs he inherited, such as a Boston College team that had gone 4-7 the year before he was hired in 1991.

“When I walked into the training complex at Boston College for the first time, the team was in the middle of an offseason conditioning workout. I watched for a few minutes, and suddenly one of the players just got up and walked into the men’s room,” recalled Coughlin. “I followed him right into the men’s room, questioned his commitment, and then dragged him out. I called the team together and told them, ‘My name is Tom Coughlin. I’m your new coach. I’m not here to make friends. I promise you this: When you leave here, everything in your life is going to be easier than this.’”

Based on the way they allowed the 2019 season to end – with three blowout losses and an overall whimper – the current Panthers can probably afford to be smacked around a little by Matt Rhule. And while Rhule can’t run the sort of two-a-days Coughlin once did (two-a-days were eliminated in the 2011 Collective Bargaining Agreement), toughening the Panthers back up is going to take a level of heavy-handedness: pushing players harder than they think is necessary, not letting mistakes slide or tolerating excuses, and reading the riot act when the situation calls for it.

That strictness in getting a team to perform like it should has its uses: under Coughlin, star Giants running back Tiki Barber went from being careless with the football and fumbling frequently to a paragon of ball security and an All-Pro.

However, there’s a very fine line that Coughlin found, and one that Rhule should try and avoid.

Coughlin’s reputation as a crotchety old tyrant followed him to New York, and his ways ended up alienating veteran players like All-Pro defensive end and team captain Michael Strahan. And although the Giants were once again a playoff team by 2006, they were bogged down by penalties and overall issues with discipline. Coughlin’s Giants went 0-2 in the playoffs, and Coughlin himself barely avoided being fired after his third season.

In order to survive, Coughlin had to change his ways and become less rigid and more open in how he dealt with his personnel. But although he began to loosen up and allow his players to see a friendlier side of him, Coughlin did not change or make compromises on his core values and the values of the structure he had built – it was that decision that helped Coughlin’s Giants win their first Super Bowl only one year later.

“The willingness and the ability to change is essential. That doesn’t mean changing with the tides, going in and out all the time,” wrote Coughlin. “You have to establish your principles and stick to them while also finding a way of making what you do relevant to the people you’re working with … I haven’t changed my core values, I haven’t changed my coaching philosophy, I didn’t change my personality, and we haven’t changed our core culture. Everything we do emphasizes teamwork, hard work, and attention to detail.”

“But what did change was that I found a better way to express myself, and I adapted to the changes in the environment around me. Those changes made a big difference.”

Inevitably, there will come a time where Matt Rhule will be faced with a similar situation where he needs to adapt and do something different: Whether that’s adopt a new way of playcalling when another isn’t working, make a change to the lineup, or make a change on his coaching staff. But such actions will only be effective, as they were for Coughlin, if Rhule remains true to his beliefs as a coach.

Build An Organization With Character

Photo Credit: Bill Kostroun/Associated Press

On the surface, this seems a trite and cliched statement.

Of course all NFL teams want to build teams centered around players with high character. But building a team full of individuals that reflect the values of a franchise is a much tougher task than it’s given credit for. And Tom Coughlin was particularly successful at weeding out those who fit from those who didn’t.

As part of his disciplinary style, Coughlin’s rules were simple: If any player broke the rules of the team, no matter how big a star or minute the infraction, there would be consequences. And those consequences, indeed, had teeth: In 1996, Coughlin cut star wide receiver and prized free agent signing Andre Rison after issues with his attitude and approach on and off the field. In December 2011, just before a critical divisional game that would likely determine the Giants’ playoff fate, Coughlin benched star running back Ahmad Bradshaw for the entire first half after he missed curfew.

Coughlin himself acknowledged that the highly-structured system that his teams followed weren’t for everyone – Particularly not those who needed more flexibility or individual freedom. But it was that structure – and the character required to succeed within it – that allowed Coughlin’s teams to persevere the way they did, even with the deck stacked against them.

“Almost inevitably there are going to be situations in which character will make a significant difference,” wrote Coughlin. “When you’re dealing with adversity or you have to sacrifice personal achievement for the good of the team or you aren’t getting the opportunity you think you’ve earned, you need to have a personal reservoir of character to draw on.

“As a coach or a manager, you want to work with dedicated people who have values similar to your own, people you can depend on to be there when things get tough. The more of those good character people you have in key positions the better chance you have to succeed.” (p. 51)

It’s no accident that those players who embraced Coughlin’s structure succeeded in it: Wide receivers like Jimmy Smith, Keenan McCardell, and Victor Cruz went from roster afterthoughts to superstars. In the Giants’ two Super Bowl wins, two of the biggest difference makers were core special teamers in wide receiver David Tyree and linebacker Chase Blackburn – who you might know now as the special teams coordinator of the Panthers.

In trying to instill character within his Panthers, Matt Rhule has quite a bit of work cut out for him: a mass exodus of many of the franchise’s vested veterans has left a leadership and character void both in the locker room and in the community. And in their place, Rhule has rolled the dice on players who bring some baggage with them to Carolina: namely wide receiver Robby Anderson (multiple arrests, which included charges of threatening to assault a police officer’s wife) and cornerback Eli Apple (major maturity issues and team-issued suspensions on the 2017 Giants).

Building a strong core of high-character players will help the Panthers sort out certain issues without the head coach having to intervene. But invariably, Rhule will run into a situation where he has to take a stand on preserving his team’s character, even if it means crossing a star player or someone who the team “needs” in order to win.

Should he prove as uncompromising as Coughlin was, he may be looked at cross-eyed and met with criticism – such as when Ron Rivera benched Cam Newton for the opening series of a 2016 game due to a dress code violation in the previous generation of Panthers football. But if that ends up being the case, it will benefit Carolina in the long run, ensuring that the structure and values that Rhule establishes are not undermined and his team does not fall down the slippery slope of letting things slide.

“If you are in a leadership position in any organization, in any job, and you compromise your principles the first time you face adversity, you’ll lose all your credibility. After you compromise once, who is going to believe you the next time?”, wrote Coughlin. “The entire structure suddenly becomes shaky. Your word has lost its value. … Earning the right to win means making a difficult or even unpopular decision and sticking to it. The principles and values that form the cornerstone of our beliefs cannot be compromised.”

Interestingly, the very end of Coughlin’s coaching career illustrates this point. Late in the 2015 season, the signal that Coughlin’s time as Giants head coach was up likely came in a game against the Panthers, when he did not bench wide receiver Odell Beckham Jr. despite his star wide receiver losing control and fighting with cornerback Josh Norman. Although keeping Beckham in the game gave the Giants a chance to win, it ultimately didn’t pay off, and sparked a sequence of events that would see both Coughlin lose his job at the end of the season and Beckham’s own Giants career unravel.

Effort Begets Belief. Belief Begets Defying the Odds.

Photo Credit: Al Bello/Getty images

One of the greatest characteristics of the previous generation of the Panthers was how they performed – and prevailed – against the toughest of competition. Instead of cowering before the elite of the NFL that challenged them, Ron Rivera’s teams challenged the teams weren’t supposed to beat right back. That sort of resolve, odds be damned, is what helped the Cam Newton-Ron Rivera teams go 2-0 against the mighty New England Patriots dynasty – you’ve probably heard that stat a lot over the past week.

That strength was also a strength of Coughlin’s teams, who were responsible for some of the greatest upsets in Pro Football history. In the 1996 playoffs, Coughlin’s Jaguars ended the Buffalo Bills’ AFC dynasty of the 1990s, and then stunned the No. 1 seeded Denver Broncos in the Divisional Round. Ten years later with the Giants, Coughlin served at the helm of Big Blue’s defeat of the undefeated Patriots in Super Bowl XLII. But lost in that accomplishment was a certain act by Coughlin – one that went against the tide of what was expected – that made the Giants unafraid of who stood between them and being world champions.

By Week 17, the Giants had already secured their spot as the No. 5 seed in the playoffs, and hosted the Patriots as they sought to finish the regular season a perfect 16-0. In the eyes of the outside world, there was no point in the Giants trying to win the game: Many would have had them simply rest their starters and concede what was a “meaningless” game for them.

The game turned out to be anything but “meaningless”: Coughlin had the Giants’ starters play the Patriots and play them hard in what turned into a back-and-forth thriller. Though the Giants ended up losing 38-35, the game would end up becoming a seminal moment in their Super Bowl run, as it armed them with the knowledge that they could take it right to a team that was on the verge of being crowned as the greatest in NFL history.

“It turned out to have been an extremely important game for us. We’d lost the game, but we’d gained a lot,” wrote Coughlin. “After that we knew we could compete with New England. Many players said, ‘if this is the best team in the league, we have a real good shot to win it all.’

Without question, when we played them again several weeks later in the Super Bowl, the confidence we had gained that day certainly contributed to our 17-14 victory.”

Considering that Matt Rhule now has to build the Panthers up from the bottom, getting his players to believe that they’re just as good as the best in the NFL is going to be critical to his success as head coach.

In football, as in life in general, success in the face of adversity is often determined through attitude. If a team enters a game against a top team with thoughts like “We can’t keep up with these guys. There’s no way we can compete. We’re going to lose!”, they’ll inevitably see that prophecy be self-fulfilled. But if a team has the right attitude – “We’re not going to just bow down and take it. We can beat these guys!” – they might just have a chance at being triumphant.

To that end, Rhule’s first challenge will be to make winning the gospel and ultimate revelation – Which won’t be easy in Year One, as he will have to keep the “T” word out of the locker room and all the toxic ideas – namely ideas like “You shouldn’t win this game, you won’t get as good a draft pick if you do” – that come with it. The first step towards that will be for him to see to it that his players put forward a complete effort no matter what the circumstances, and no matter what anyone else thinks.

“Giving less than a maximum effort would have contradicted our entire philosophy and compromised our credibility,” wrote Coughlin of his Giants’ Week 17 prelude. “The essence of competition is giving your best effort.”

Be Yourself

Photo Credit: Ron Jenkins/Getty Images

At the risk of contradicting all that has been written before this, there is a critical point that needs to be made: Matt Rhule is not the second-coming of Tom Coughlin. Matt Rhule is the first-coming of Matt Rhule.

When an apple falls from a notable coaching tree and onto a new team, it is easy to fall into the fallacy (as perhaps New York did in hyping Rhule as the next coach of the Giants) of assuming that the student is a carbon copy of the master. Counteracting this, of course, are countless examples of failed disciples of successful head coaches. And Coughlin, by no means, was immune to this trap himself.

Once upon a time, Coughlin was a disciple of Bill Parcells, a Pro Football Hall of Fame coach and a larger-than-life figure in New York football. A New Jersey native who spoke as he found, Parcells was famously sharp-tongued and abrasive – Especially with the media, a group which he once ribbed as being “commies … subversive from within, even when it’s going good.”

Like Parcells, Coughlin took the approach of being curt with the press. But at the end of the 2006 season, he realized that he had erred in trying to emulate the man he had once worked for.

“I could pull some of the Parcells stuff – But I couldn’t get away with it,” recalled Coughlin on NFL Network’s A Football Life. “I wasn’t Parcells. … I haven’t had enough success for them to put up with this guy.”

As a result of his handling of the New York media – a group not particularly known for being coach-friendly – Coughlin found that he had almost no allies in the press corps, most of which were leading the cries to fire Coughlin after his third season.

At the urging of his family and others he confided in, Coughlin smoothed over his relationship with both the press and his players. And as it turned out, that would be a turning point in Coughlin establishing a Giants legacy that was all his own.

Some of the challenges that Coughlin faced won’t be experienced by Rhule at quite the same level. Still, he has a lot to live up to as head coach of the Panthers: Not only does he come to the Panthers with hype and the distinction of being a member of an esteemed coaching tree, but he also has a tough act to follow: Ron Rivera was the most-successful head coach in Panthers history, and the presence he had both on the sidelines, in the community, and in hearts and minds will not easily be replaced.

Though he never served on one of Parcells’ staffs, Rhule nonetheless has spoken of being a Parcells acolyte. In a recent column by NBC Sports’ Peter King, Rhule spoke of several lessons he learned from studying Parcells – Namely being a “walk-around coach” and the importance of field position.

Still, Matt Rhule cannot be Bill Parcells. And he can’t be Tom Coughlin. Not if he hopes to succeed as an NFL head coach, where the only merit one can get by on is his own.

But regardless, anything that Rhule can glean from the examples of his predecessors can be to the benefit of both him and Panthers football as a whole. Should he end up succeeding as Panthers head coach, part of that success will be the use of lessons learned from some of the best to have ever gotten 53 individual men to play as a single team with a unified vision of championship football.

In his time, Tom Coughlin was indeed a master builder, motivator, and leader. And if Matt Rhule fulfills all those same qualities, he and the Carolina Panthers will have met the lasting mantra of Coughlin’s championship ways.

“The path to success begins with deliberate, determined preparation. Having this structure will help you keep focused, it will provide the confidence you need to keep moving forward, and when you finally get there, it will give you the tremendous satisfaction that you have earned the right to win.”

(Top Photo of Tom Coughlin: Mark J. Rebilas/USA Today Sports)