So What Do I Do Then?

My attempts to remove these biases lead to the main source of discrepancies between myself and other evaluators, or at least does in my opinion; the first is in the understanding of the actual probabilities of a player making it in the NFL:

“We overestimate how likely it is for a young player to become a contributor to a professional team because it is easy to think of examples of professional players. Scouts should be aware of the base rates, for example how likely it is for a drafted player to play in the league for at least 5 years. The numbers of players in a particular draft class that a scout predicts will be valuable NFL contributors should be close to the base rate, allowing for some variation.”

As has been shown by the numbers early in the article, there probably aren’t as many great prospects as many evaluators think; a number of the players being discussed among the top in the 2018 Draft will bust, and many NFL scouts have simply failed to account for this in their grades. If we are now to examine how many draft picks (not just first rounders) become good NFL players then we need to change our ratings somewhat. If 5 AV is the grade for a first rounder not being a bust, then what is a good grade for a successful first round pick?

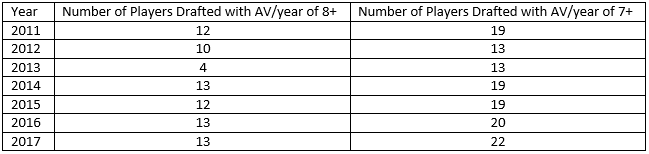

For this, I am going to use a rating of 8, again fairly arbitrary, but seems at about the right level. Devin Funchess and Trai Turner each received this rating last year, which seems a reasonable estimation of a good player worthy of a first-round pick. 13 rookies last year had an AV or 8 or more, but there is an understandable learning curve, so what if we look at the AV of players over a series of drafts?

Some things become very clear from this chart: the 2013 draft was terrible and; that there simply aren’t as many good prospects as most people think. While there might be slightly more than this suggests due to either games missed due to injury or those who take a year or two to develop before contributing, from a pure value standpoint there are not 15 great players in most drafts and certainly not 32. While there are some players that bust for reasons that are not to do with football, it would seem that based on these numbers there should be no more than about 25 players graded as being worthy of a first-round pick. After all, these picks are meant to be nearly sure things.

However, Draft Scout currently has 39 players with first or borderline first round grades, Walter Football has 45; I have 14 (so far). That, of course, doesn’t make my assessments any better than other scouts, but merely that the far fewer number of high grades is in an attempt to better reflect the actual data. There is, of course, the issue of potential, the idea that a number of players are drafted based not on their abilities but instead based on what they have the potential to become; I have attempted to account for this as any other scout would, but with knowledge of the number who ever actually reach a certain level of production, it’s hard to account for this uncertainty based on this idea of potential, thus you end up with the Josh Sweat situation of a Round 2-3 grade and a Round 1 mock.

The final source of error I have been extremely conscious of is the influence of extraneous factors:

“Our predictions are skewed by unimportant factors, such as what the player looks like, and what team they played for. It is easier to imagine a short, white, slot receiver to become a successful professional because of the success of Wes Welker and others, but it is difficult to imagine a short, black, quarterback from succeeding in the league because of the lack of players that come to mind. It is also easy to imagine a LSU cornerback becoming a lockdown corner and maybe we distrust Alabama quarterbacks because there haven’t really been any good ones.”

It is all too easy to see something on tape which reminds us of a current or former player and to stretch the limits of that comparison leading to a distortion of the player’s performance in our minds. In order to combat this, it is important to build a detailed picture of what it is that determines a player’s ability at a given position and to ignore factors which do not fall into these categories and to include those which do; if you can do this in a disciplined fashion and try and limit the number of outside biases you bring to your evaluations, then your evaluations will become more objective. By forcing yourself to focus on the good and bad of every player to as great a degree as possible, a more complete picture is obtained.

Photo Credit: Joe Robbins/Getty Images

For many evaluators, the biggest imported bias is that of a knowledge of others’ opinions on that prospect. Depending on your views of those other scouts, this can bias your viewing of the prospect either for or against them leading to a false gradation; it can be very hard to agree with somebody you think is often wrong on a prospect or, more commonly in my experience, disagree with somebody whose opinions you respect. However, this is a vital part of player evaluation and in this regard, I do my utmost to not look into other evaluations of a player until after I have watched and only use other evaluations as challenges to my own in an attempt to avoid importing biases unfairly. Thus we end up with the issue of Quenton Nelson.

Quenton Nelson is unquestionably the highest regarded offensive lineman in this draft, with some going as far as calling him the best guard prospect ever. However, what I see on tape raises enough questions that I cannot say that I agree. The biggest flaw with Nelson in my opinion is his balance, especially in the run game; while he is very powerful, he doesn’t always control it very well, leading him to play with a significant forward lean. While this has landed him on the floor a lot in college, it will be potentially even more significant in the NFL where tackles are generally better. Dontari Poe, for example, has developed a reasonably effective punch-rip to catch linemen off balance and it would be hard to image that not being extremely effective against Nelson. I’m not saying that nobody else has noticed this, or that it is some great conspiracy, but rather that because Nelson is seen as a top prospect, people watching him for the first time come into his tape with the preconception that he is going to be good and unconsciously underestimate his flaws. This doesn’t mean that Nelson is destined to fail at the NFL level, but that his range of outcomes might be a lot broader than many claim; the best part about draft scouting is that there will be an answer, either I will be right and Nelson will not live up to his draft status or I will be wrong and can adjust my scouting for the next guard prospect; scouting is a consistently fluid exercise and to not realize when you’re incorrect and adjust your template for success would be facile.

There is therefore no seismic change in the way I evaluate talent, but rather a greater awareness of the flaws which I and others are likely to fall down, as well as a knowledge of the data behind the accuracy of evaluation. Crucially, as with every other evaluation you will read, mine are merely opinions, which will, of course, often be wrong; all that really matter is whether I am wrong more or less often than the other NFL evaluators.

Now you know, and now you can imagine the phrase “I think…” in front of every sentence of every evaluation. I think that’s only fair.

things such as spacial recognition and reaction time are important… too many tests are static and not enough are dynamic… high pressure functioning and failure tolerance are also important things to test more specifically