This article might not be filled with sunshine and rainbows – and while I think it is important that the Panthers face up to the unpleasant realities of their issues, this is something that should be done in the least painful way possible; therefore, before we go into the details of how the Panthers managed to lose a game where they entered the final two minutes with a first down in the opponents’ half of the field without even needing to go to overtime, let me tell you a quick story to ease you in.

You may not know this, but I’m British – coming from the UK, American football was not a sport I was hugely aware of growing up, and the vast majority of my childhood sport-watching was spent watching rugby which, living where I did, meant watching London Irish. For as long as I can remember, Irish were charmingly incompetent, and while it took a while for me to warm to this style of rugby, I slowly moved from amused bystander to fan. For the past three seasons, I have attended almost every home game with my father and grandfather, and so when they found themselves in a relegation battle this past spring, I actually cared quite a lot about the outcome.

At one point, they actually managed to make me believe they could do it, with wins against Worcester and Harlequins putting them less than two games back, and many other fans started to believe, and so, when the reigning champion Chiefs came to visit, the ground had something of a cup-final – or playoff – atmosphere.

They lost 45-5.

Not only did they lose, but from about the tenth minute on, they looked completely overwhelmed – by halftime, the game was as good as over. I, like many of my fellow fans, were understandably saddened by this – but what I wasn’t, not even for a second, was annoyed.

This was because what had caused Irish to lose wasn’t their usual mindless errors or a last minute fumble, but rather the fact that the Chiefs played the best game of rugby I have ever seen. I would show the highlights here, but they simply cannot do justice to the fact that, for the full eighty minutes, the Chiefs did not make a mistake or even take a misstep; I honestly don’t think there is a team in the world that would have beaten them that day – also, because most of your are here to read about the Panthers and not watch rugby highlights – so I’ll get to the point.

I wasn’t annoyed because Irish didn’t beat themselves, they simply weren’t good enough.

I’m not sure when the Panthers last lost a game simply because they weren’t good enough, but it wasn’t this season – this is the story of a team that won’t get out of its own way, and so now that we’re done with storytime, let’s talk about how the Panthers managed to lose another game they should have won – but let’s fast forward to the final sequence, because isn’t the entire game engineered to put you in a position to win at the end?

Just One First Down

When the Panthers exited the two minute warning, they had a first down on the Seahawks’ 40-yard line in a tie ballgame. That gave them three options:

- Settle for a long field goal and try to force the Seahawks to burn both of their remaining timeouts and still run 50-ish seconds off the clock to give Russell Wilson around a minute to drive the field with no timeouts.

- Try and pick up a first down to set up a shorter field goal and in so doing, allowing the Panthers to run the clock down so at worst they go to overtime

- Finally, to try and drive the remainder of the field to score a touchdown or to set up a short field goal, almost certainly allowing them to run out the remainder of the clock.

What is confusing is that the Panthers opted for none of the above – they ran once, threw an incompletion and then settled for a short throw to set up the long field goal, while only running 15 seconds off the clock.

Let’s look at this play by play:

This is a play that perhaps should have been checked out of, but is far from a disaster. The Seahawks have seven men in the box and with Chris Manhertz motioned out to the right, they have two more box defenders than the Panthers have blockers – if this is halfway through the first quarter, you would want to check to a quick outside throw. The Panthers draw up a decent play to run the ball; despite Frank Clark playing it really well, they still pick up three yards. This isn’t a bad play, it could have been better, but second-and-7 is far from a hole – you even force the Seahawks to burn a timeout into the bargain. So far, so good.

Here, the Seahawks have everybody within ten yards of the line of scrimmage – they clearly think the Panthers are going for plan A and are looking to force them into the longest field goal possible. If you are actually committed to plan A, then you run the ball regardless, make them burn their second timeout and then try your best to pick up a first down while making sure you run time off the clock if you don’t make it. If you are going for plan B or C, however, you likely look to use a run fake to take a shot over the top. This isn’t a high percentage throw, but this defense is very vulnerable over the top and you have a speed matchup on the outside. What you don’t do, however, is run a quick passing play with all five receivers running short routes – you know, where all the defenders are. The play is made all the harder by Taylor Moton getting beaten early by Clark, but this is a play that was unlikely to work regardless.

It is impossible to know who was responsible for them being in this play against this defense, but it is hard not to bring this back to coaching.

There is a chance that Cam knew he should check out of this play against two shallow safeties and simply failed to do so, but it is just as likely if not more so, that Cam either couldn’t check to a suitable play or that it hadn’t been communicated to him what defenses should lead to what check. In an ideal world, a player would know when to check to what, but given that this is what made Peyton Manning so special, it is probably fair to say that this is a surprisingly rare characteristic in quarterbacks, in which case it is the job of the coaches to create an effective pre-snap checklist – not to mention the Panthers had two timeouts, either of which would have presented the opportunity to change the playcall.

Because none of this was the case, the Panthers were then faced with a third-and-7 which, if they converted it, would likely win them the game.

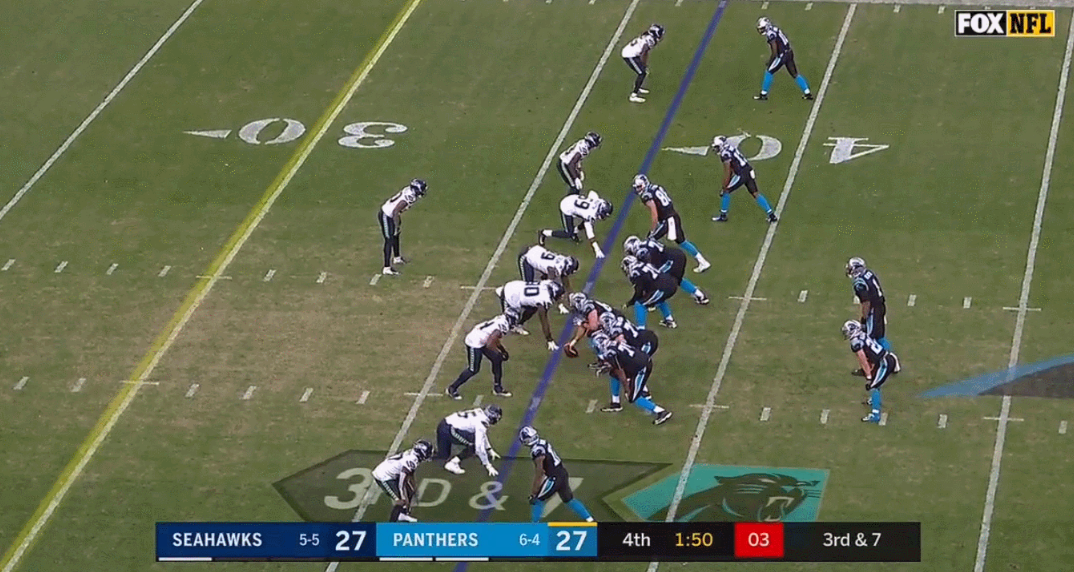

This was largely for the game, so let’s go through what went wrong piece by piece. The Seahawks are clearly in man coverage, with an extra defender showing blitz and two deep safeties. Given that this is man coverage, there are only five things that can happen:

- The Seahawks don’t blitz but don’t have a zone defender to cover the short middle

- The Seahawks don’t blitz and do have somebody to cover the short middle, leaving only one deep help defender

- The Seahawks blitz and don’t have somebody to cover the short middle, opting to cover the deep middle instead

- The Seahawks blitz and have somebody to cover the short middle but in so doing, leave the deep middle exposed

- The Seahawks drop an extra defensive lineman into coverage and only rush three allowing them to have three help defenders but likely giving Cam more time to throw.

Knowing this, how do you attack?

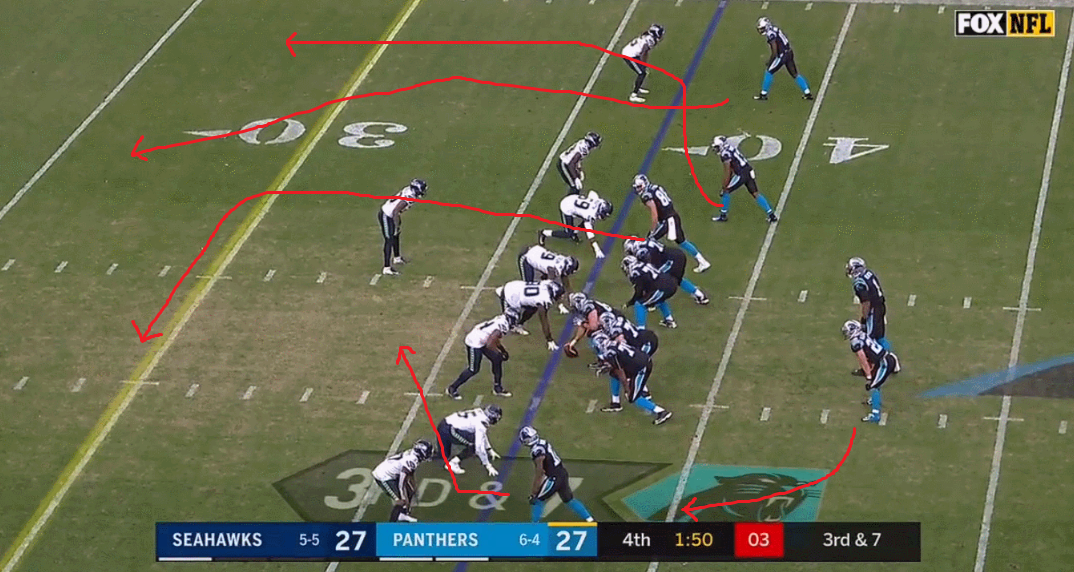

The first thing you do is that you attack the short middle. This is the easiest place to attack and, if a team does blitz in man coverage, has a roughly 50/50 change of being wide open. Second, you attack the deep middle, this accounts for the other 50% in the man-blitz scenario. Third, you attack the flats, as these are unlikely to be covered by any help defenders, and give you an easy completion if nobody drops down to cover the running back in case of a blitz. Finally, you attack the deep outside. This is the throw you least want to make, because it is likely to be the hardest, but if a team plays effective man coverage with help over the top and in the short middle, this is the only place left to go to. Given all this and the Panthers’ formation, a sensible play may have looked like this:

This gives you a concept to attack the blitz on the near side, with a levels concept to attack a single-high safety look where the underneath safety takes away the slant; part of the key to this is Olsen getting far enough outside his man before breaking back that he is forced to turn his back on the quarterback in order to open up the space for the slant. The progression would be McCaffrey-Moore-Samuel-Olsen-Wright. If you’re feeling fancy, you could add an option route to the end of the swing pass. This, as you have probably guessed, is not what the Panthers ran. They ran this: