No position is as valuable to an NFL franchise as the quarterback position. Great quarterbacks can turn otherwise mediocre rosters into winning machines, and this is born out in the draft, with quarterbacks being at a premium early in the first round especially. Already this offseason, the 49ers have shown what it can cost to move from a top-15 pick to being able to select the third quarterback off the board.

While the Panthers’ trade for Sam Darnold has decreased their chances of selecting a quarterback with the eighth pick, this shouldn’t be ruled out entirely and the Panthers are still very much on the lookout for their long-term answer at the position.

Michael Reaves/Getty Images

One very real possibility is looking to select a quarterback at some point in the middle rounds, but is this a good idea? To answer this question, we first need to answer two important questions: Do NFL teams find value in these picks? And what are the chances you can find the next Russell Wilson or Dak Prescott instead of the next Will Grier?

We’ve taken a look at the data to find out.

To take a look at where quarterback value may lie in the NFL Draft, we first need to decide on a measure of quarterback “success” in the NFL. The measure we will use incorporates Pro Football Reference’s Approximate Value (AV) which gives a rough approximation for how valuable a quarterback is in a given season.

As we want to be able to incorporate current players in our data set we can’t use career AV, and we also want a metric that allows us to account for the fact that some very good quarterbacks such as Aaron Rodgers and Patrick Mahomes don’t start right away. To do this, we are going to use the summed AV of the three best seasons a quarterback has in their first six seasons.

After six seasons, players should have had enough time to establish themselves as a starter and using the sum of three seasons prevents one outlier season one way or the other having an overly significant effect. We shall refer to this metric Adjusted AV (AdjAV).

The data set used includes the drafts from 2003 to 2015, which gives a sample size of 160 which is suitable for the kind of analysis we want to do. More recent years cannot be used as the AdjAV metric requires each draft class to have completed six years in the NFL.

To give a sense of scale, Kyle Allen had an AV of 7 for his 2019 season, Teddy Bridgewater had an AV of 12 for the 2020 season and Cam Newton had an AV of 20 for his 2015 season.

This group is led by Cam Newton (55), closely followed by Philip Rivers and Russell Wilson (both 54) with Matt Ryan (49), Aaron Rodgers (48) and Andrew Luck(47) following at a slight distance. While not everybody who started off hot, such as Blake Bortles (16th, 37), managed to sustain that, overall this group does pass the eye test, and it’s good to see that the likes of Tyrod Taylor (28th, 29) are still picked up despite not playing much early on.

Photo Credit: The Associated Press

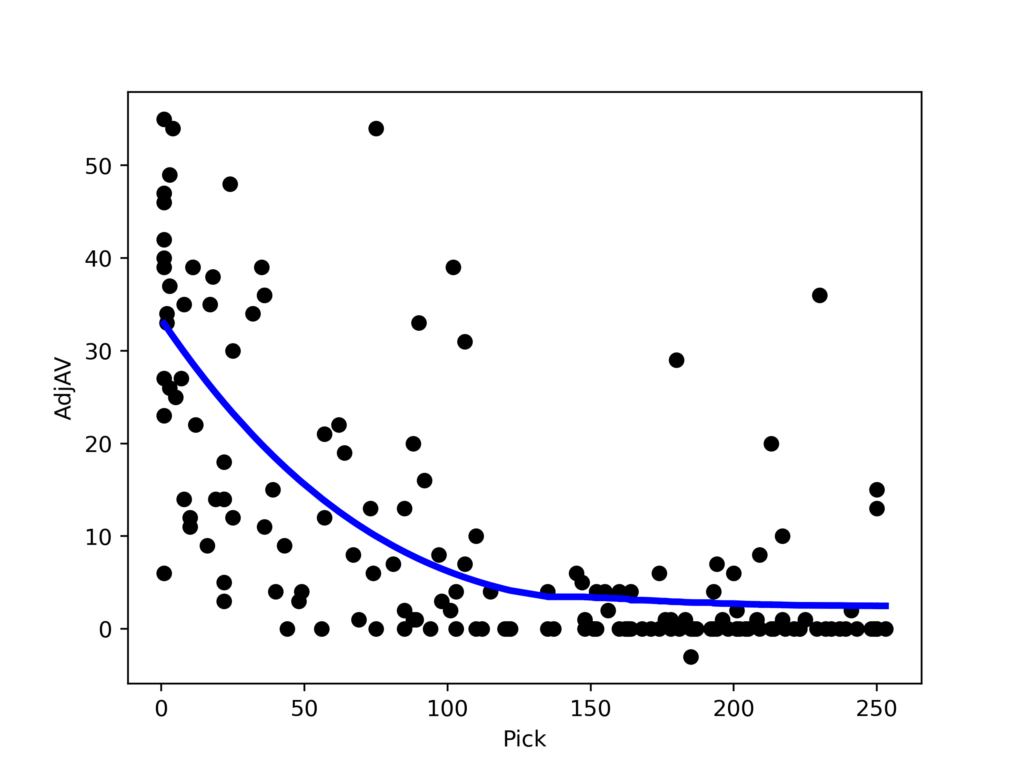

Firstly, let’s look at how AdjAV depends on where a quarterback is selected, which has been fitted to indicate a general trend:

Unsurprisingly, the higher a player is selected, the higher their AdjAV. It is worth noting, however, that this data doesn’t exactly follow the fitting, and so in order to judge how effectively outcomes correlate with picks we are going to go back to looking at R^2 values, which are explained in the first article in the series. Here, the R^2 values is 0.52, and this is something we’ll come back to later.

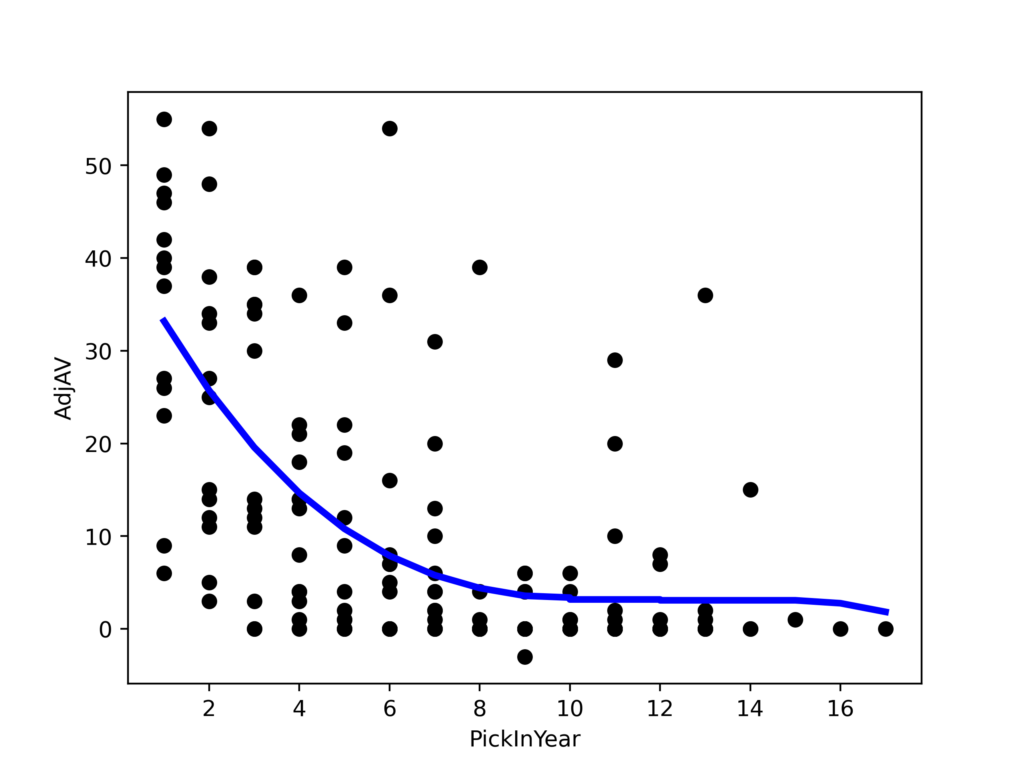

Before that, however, it is also worth looking at how AdjAV depends on the order in which quarterback prospects are selected. This allows us to explore whether there is a meaningful difference between drafting the third quarterback off the board with the third pick as opposed to taking the top quarterback off the board with the third pick.

Unsurprisingly, and to the relief of the NFL scouting community, the later a quarterback is drafted compared to the others in their class the lower their AdjAV. However, the R^2 value is 0.42 meaning that the order in which quarterbacks are selected is less of an indicator of their success than where they are drafted with respect to their draft class as a whole.

Ok, so yes, quarterbacks selected first overall are on average better than those selected in the fourth round, this isn’t exactly a surprise. To get more usable information, we need to look at whether the probability of hitting on a quarterback decreases more or less quickly than the valuation placed on picks.

To do this, we can split it into separate buckets based on where they were picked. These buckets can then be used to present the AdjAV of each pick in an easier to digest way. Given the dataset has 160 players, a decision was made to split it into 8 groups of 20 players, segmented by where they were picked.

There is a group of around 20 players that were picked between 1 to 10, 20 players that were picked between 11 and 36, and so on. For each group, we can then look at the median AdjAV, and also the percentage that achieved an AdjAV of 39 and above, and an AdjAV of 33 and above, which roughly corresponds to the top 10 players and the top 25 players respectively.

| Picks | Median | %AdjAV >= 39 | %AdjAV >= 33 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to 10 | 34.5 | 40 | 55 |

| 11 to 36 | 20 | 20 | 45 |

| 37 to 85 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 86 to 112 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 113 to 162 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 163 to 193 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 194 to 217 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 218 to 255 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

The first thing to note is that non first round quarterbacks rarely become good players. Of the 120 players that were drafted from pick 37 onwards, just 5% achieve an AdjAV of at least 33 (For reference, Marcus Mariota has an AdjAV of 34). So, of course there’s a chance you pick Russell Wilson, but that chance is tiny. It is also worth noting that the median AdjAV for players picked 113 and later is zero. Another way of putting this is that late round quarterbacks will not see the field at any point in their first six seasons.

The more interesting thing to look at is the difference between the first bucket (picks 1 to 10) and the second (11 to 36). This gives us an indication of whether you really need to spend a high first round pick on a quarterback, of whether it is better waiting until the end of the first round. The chance you get an OK starter (AdjAV >= 33) is roughly the same, at 55% and 45% respectively. But the chance you get a good starter (AdjAV >= 39) is different: 40% for the first bucket and 20% for the second. So if you only have one first round pick and want a good quarterback, your chances are a lot better if it’s a top 10 pick.

Based purely on these numbers then, a team with a top ten pick that trades back for a late first-round and very early second-round and spends both on a quarterback would likely have the same chance of finding a high-quality starter as if they spent their top-ten pick on a quarterback, but this fails to account for the pragmatic issues with effectively developing two young quarterbacks simultaneously, let alone the likely backlash from the fanbase of any team to actually try it in practice.

Photo Credit: STEW MILNE/ASSOCIATED PRESS

One further thing to look at is whether in drafts featuring lots of quarterbacks in the first round, those that get picked at the end of the first round are undervalued. The rational behind this would be that if they were in a weaker quarterback draft they would be picked higher.

To look at this, we can take quarterbacks picked from 11 to 36 and exclude those that were among the first two quarterbacks picked in that particular draft. This leaves 8 players. Of those 8 players, the median AdjAV is only 20, and only 3 have an AdjAV of 33 or higher. The best of these players is Ben Roethlisberger (and even then he was picked 11 overall). The worst are Christian Ponder, Rex Grossman, and Brandon Weeden.

Yikes.

Including Lamar Jackson would help the valuation of these picks (he was drafted in 2018 and so wasn’t included) but not enough for there not be be a clear drop-off after the top ten picks.

What this data therefore tell us is that in order to have a high chance of landing a top-tier quarterback you have to take them in the top ten, and even then you only have a 40% success rate.

However, with that said, what is also worth examining is the approach where, rather than taking a quarterback at 15 or 25 and developing them for a few years, you draft a quarterback towards the end of the second day, or even early on the third day, and do this every year regardless of your quarterback situation. This obviously will lead to a lower chance of success with any one pick, but by giving yourself more chances you might have a higher overall chance of hitting.

According to the data, historically NFL teams have had the same chance of getting a top-10 quarterback from a top-10 pick as they would have if they drafted eight players in the 86 to 112 range. From a value standpoint this approach could therefore have some merit. If we examine a pick value chart we can see that the difference in value between the 10th pick and the 86th pick is a factor of 8.75. This mean that in terms of the probability of hitting on a top-tier quarterback, quarterback picks in this range could be undervalued.

One caveat to this is that given the number of successful quarterbacks picked in this 86 to 112 range is so small, it is difficult to establish the true percentage that will become top 10 quarterbacks. For example, all it takes is one more player to reach the threshold in the 86 to 112 range for the percentage there to jump to 10%. Similarly the true percentage may be much smaller, and hence players in this range are actually overvalued.

But what does this actually mean in practice, away from the hypotheticals?

Well, given the much higher hit rate for quarterbacks selected in the top ten and the fact that most franchises can’t afford to run through eight quarterbacks, teams with top ten picks should definitely look long and hard at selecting quarterbacks. For the Panthers, this means that while they already have Sam Darnold, if there is a quarterback on the board with the eighth pick who they think if worthy of that selection then take him.

However, what is also means is that if teams are looking to find value outside of the very top tier of quarterbacks then there are indications that it will come either late in the third round or early in the fourth. Obviously, the number of players who work out in this range is very small, but so is the relative cost associated with such a pick.

Finally, in terms of conclusions from the data, it is generally unwise to draft a quarterback past the top of the fourth round expecting them to ever become anything more than a backup. Yes, Tom Brady was selected in the 6th round, but he stands in stark contrast with almost every other quarterback selected in this range.

Ultimately, however, player selection comes down to individuals, and while teams would be wise to bear this data in mind when looking at long-term strategy, you have to evaluate the players in a given class and come to your own conclusions. Selecting a quarterback in the top ten because of the data and not what you think about them as a prospect is very bad idea. Similarly, passing on a quarterback who you rate extremely highly with the 11th pick because the data suggests this is poor value would be foolish as well.

From a strategic standpoint, the two windows of value are the very top of the draft and potentially late on day two/very early day three, with players selected from the middle of the first round through to the early third round showing comparatively limited return on investment. For teams in need of a quarterback, the headline advice is really quite simple.

If you can, take an elite quarterback prospect early but, if not, target quarterbacks later on day two and hope for the best.

(Top photo via Michael Reaves/Getty Images)