The NFL really isn’t that complicated a lot of the time. In fact, it is oftentimes very simple and obvious. An example of this is the varying difficulty of throwing the ball to the various parts of the field. The Panthers, for example, completed less than 40% of their deep passes this season, around the league average, but completed well over 60% of their short passes, which is actually below the league average. This really shouldn’t be a surprising; it’s harder to be accurate when throwing over thirty yards than it is throwing five.

The next step in this logical progression is that it should be easier to throw the ball to the short middle than anywhere else on the field, as this is the area the ball has the shortest distance to travel. This is born out in the numbers, with the NFL average completion percentage on short-middle passes this year being just under 70%, with an average gain per-attempt of 7.4 yards. It should be no surprise that some of the league’s best offenses look to attempt a high number of passes to this area, especially on pivotal downs where completions are crucial.

Since Cam Newton entered the NFL, teams that have thrown consistently into the short middle have tended to be successful; the Ravens (who rank first in attempts over this time period), Giants (second) and Patriots (fourth) have won four of the six Super Bowls since 2011. The Seahawks and Broncos, the other two teams to win Super Bowls in this period; did so with two of the best defenses seen in the modern era. Additionally, offenses helmed by Kyle Shanahan, arguably the best offensive mind in football, during this period would have ranked third; that includes a season with the Cleveland Browns. Where do the Panthers rank in attempts to the short middle during this period? 31st.

This shows up clearly when the Panthers look to pass the ball on third down. Despite ranking seventh in third down conversion rate (41.9%), the Panthers convert at just 34.5% (27th) when they pass the ball. The Patriots, by comparison, convert at 40.4% when pass the ball; and the talent-strapped 49ers at 36.8%. Over Jimmy Garoppolo’s five starts, that number has jumped to 52.6%. When looking at third-and-five and shorter, the numbers are even more striking. For the season, the Panthers convert on 46.7% of such plays when passing compared to the 49ers 54.9%; a number which jumps to 68% under Garoppolo. So how are they able to be so effective passing over the middle when the Panthers are so inept?

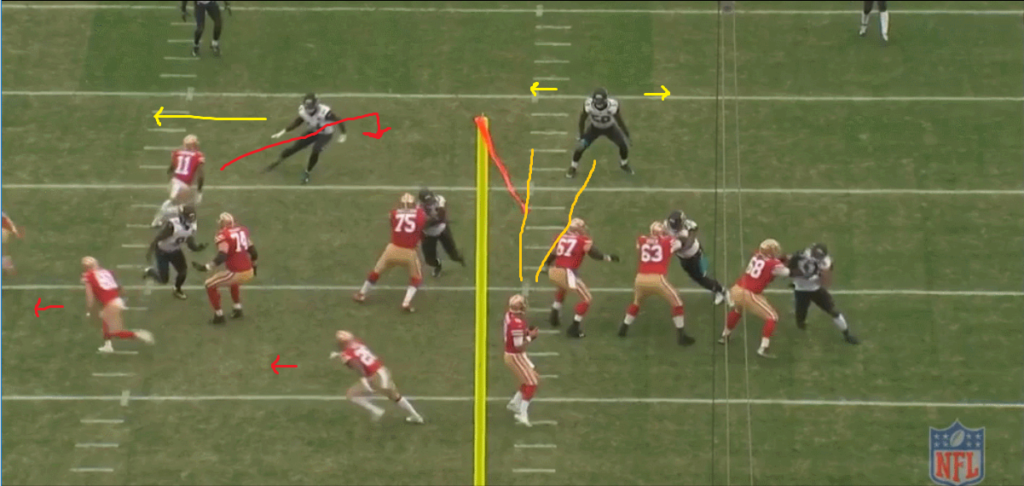

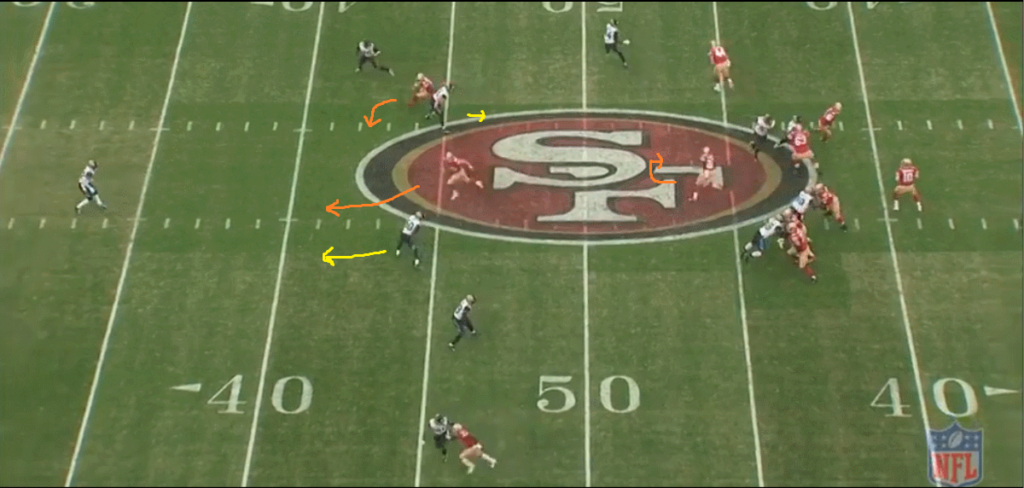

The key to much of what these offenses do is spacing, and while this concept seems more at home on a basketball court, it is also relevant to passing plays. The more of the field an offense can force a defense into trying to cover, the larger the gaps become. Against zone coverage, this makes for larger windows; against man coverage, it limits how teams can send help towards certain receivers. Generally speaking, spacing involves stretching a defense either vertically or horizontally; in an ideal world, both. The following play by the 49ers against the Jaguars is a good example of how a defense can be stretched horizontally.

The spacing on this play starts with the formation; the Jaguars adopt a two high safety formation leaving them five defenders underneath to match up with the five receivers. Crucially, the 49ers formation is heavily unbalanced, with three receivers to the left, one to the right and the running back behind the quarterback. This creates a one-on-one situation on the far side of the formation, with the three receivers on the near side forcing the Jaguars’ defense to shift that way post-snap. Aaron Colvin (#22) and Myles Jack (#44) shift almost immediately post-snap, leaving a two-on-two to the right.

![]()

The above diagram shows the read from the quarterback’s point of view, with the two backfield receivers forcing Jack (#44) outside. This leaves the quarterback to read Telvin Smith (#50); if Smith dives outside to help inside on the slant, then Garropolo can drop the ball off to the sit-down receiver and if not, as happens, he hits the slant for a first down.

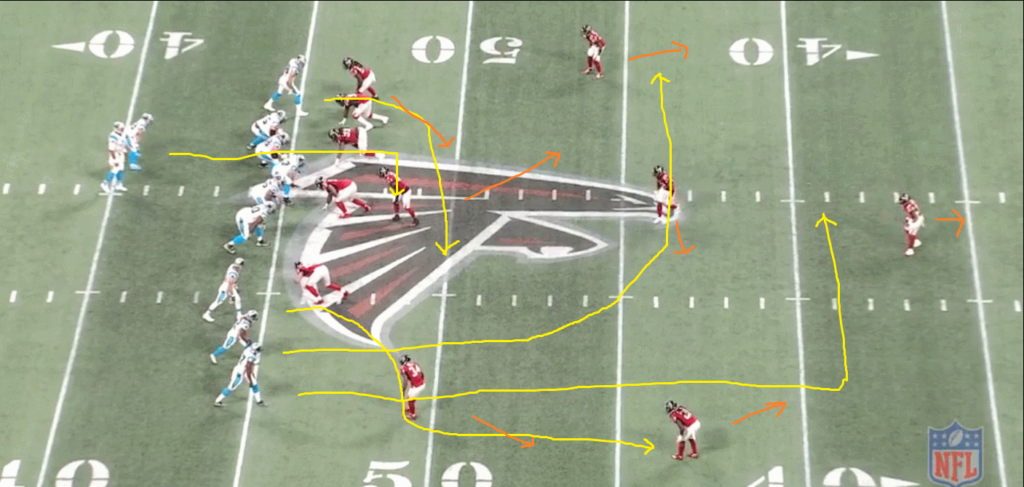

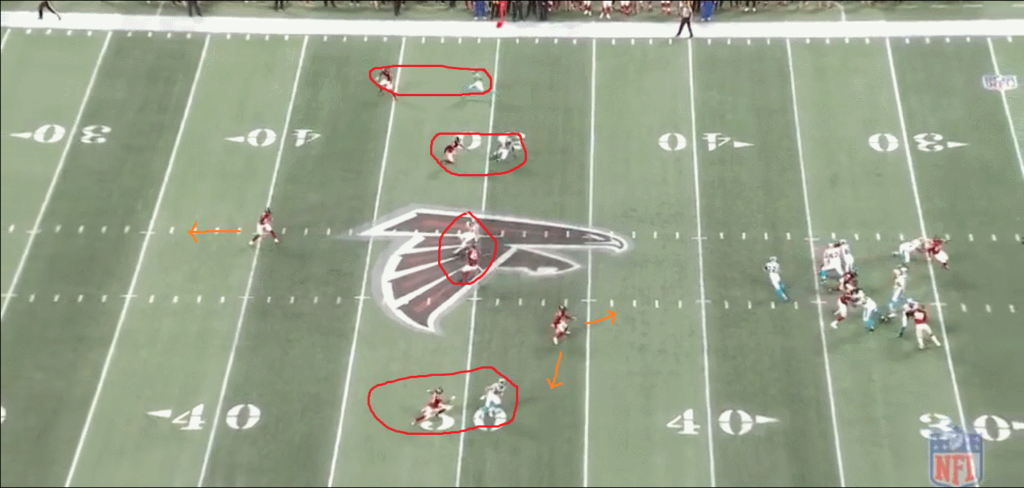

On the following play, the Panthers run a similar concept, with an unbalanced formation and the Falcons playing deep. However, in contrast to the 49ers play above, the Panthers fail to take full advantage of the width of the pitch, with all underneath routes focused on the near side of the field.

As can be seen from this clip, the Panthers allow the Falcons to completely abandon the short-left and medium-left sections of the field as both Olsen and McCaffrey drag across to the near side of the field. As shown on the following diagram, the Panthers do a good job of spacing the field vertically, but struggle with the horizontal.

![]()

The Bersin, Funchess and Clay routes force the Falcons to defend all three deep areas of the field, with the Clay, Funchess and Olsen routes also creating a layers concept over the middle of the field. Funchess forces the deep safety up the field with the two inside linebackers forced to cover both the Olsen and Clay routes, thereby leaving McCaffrey one-on-one with an outside linebacker. Whether this was an option route that McCaffery read incorrectly or whether he was meant to break inside, the net result is that the inside linebacker is able to take away both Olsen and McCaffrey routes simultaneously. Had McCaffrey broken outside, he would almost certainly have forced the deep left corner to pick between him and Clay, allowing for an easy conversion. By allowing the Falcons to only defend one half of the field underneath, the Panthers made life a lot harder for themselves than is necessary, and this leads to incompletions.

As mentioned earlier, the other way to create spacing is by stretching a defense vertically, such as the layers concept described above. In the red zone, this is hard to achieve as the field is compacted, but as can be seen on the following play, it is possible.

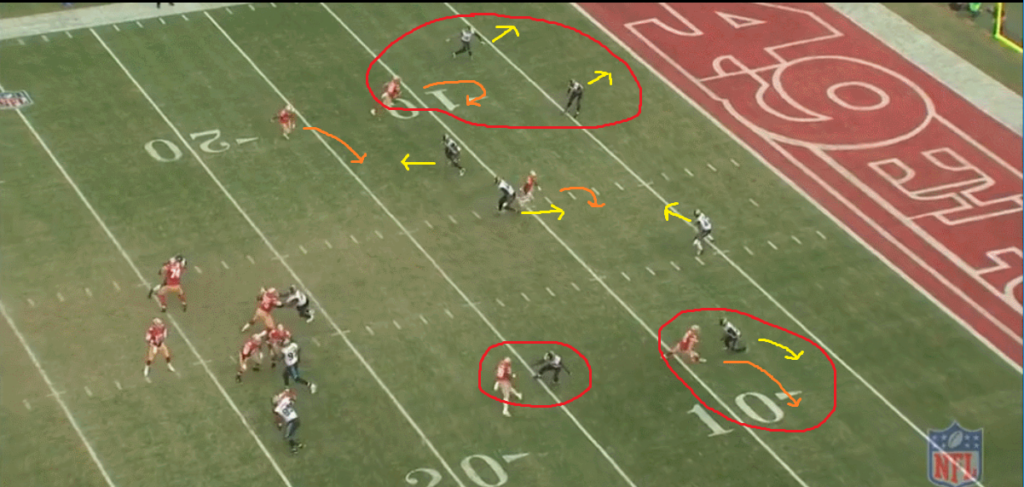

Rushing four, the Jaguars have seven defenders to cover the 49ers five receivers, but the 49ers are able to negate the advantage of the two extra defenders, as seen below:

![]()

![]()

This image is from the read point, and shows the directions of the receivers and defenders. The deep right defender is forced outside by the tight end; the deep curl on the left side hold both the outside corner and the safety, as they don’t know which way the receiver is going to break. The drag route on the far side forced the outside linebacker outwards leaving a two-on-three over the middle of the field. Here, the Jaguars chose to double the receiver drag leaving the running back in one-on-one coverage underneath, where he is able to beat the linebacker inside and makes the reception for a decent gain.

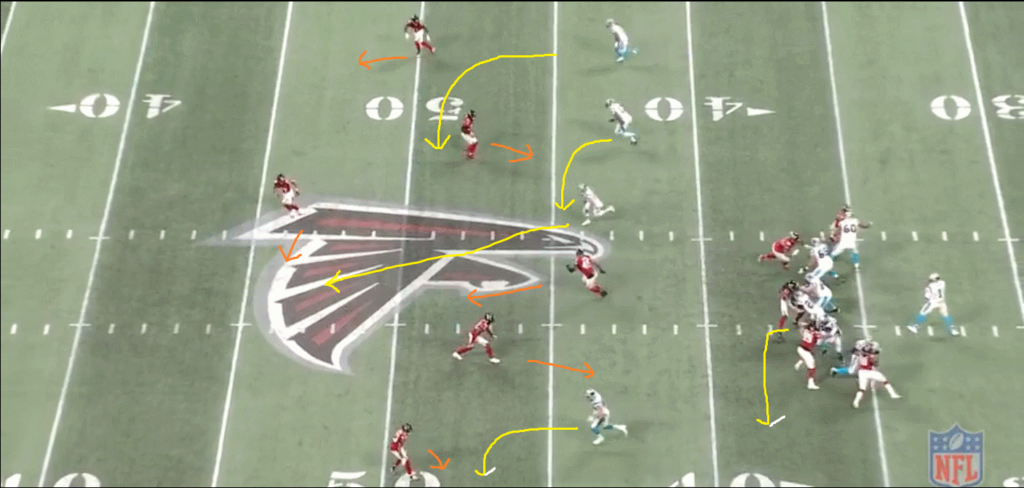

What makes this play possible is the threat of the drag route behind the linebacker and the speed advantage of this receiver over the safety. If the linebacker passes the drag route off to the safety, it likely becomes a race to the near corner with the tight end forcing the deep-right corner down the field. However, outside of the red zone, the safety is often much deeper, allowing for a more direct read on the linebacker. On the following play, the 49ers run a drag route with the running back sitting down underneath.

Again, the 49ers are able to stretch the defense both vertically and horizontally using the other three receivers, and with the drag breaking inside this creates what is effectively a two-on-one read, with the quarterback simply reading the linebacker as shown:

![]()

![]()

The tight end creates space on the inside of the linebacker while also forcing the safety deep and so as the linebacker hesitates, the quarterback is able to hit the receiver in stride. What is also important about these plays is how they place minimal emphasis on receiver ability, this allows the 49ers to have success with such route patterns without a star-studded receiver group; something that could be very relevant for the Panthers in the playoffs.

Now compare the 49ers plan of action to some of the plays that the Panther ran against the Falcons on Sunday. First, we have a Shula favorite, the five-curls play where all five receivers sit down at around 5-10 yards from the line of scrimmage, the issue with this is that with no verticality to the play the Falcons are able to sit down on those routes leaving nobody open:

Given the earlier play where the Panthers are able to use trips-right to simultaneously attack all three deep areas while also testing the defense vertically, it is clear that Shula is able to take advantage of such concepts and why he seems content here to tighten the windows for Newton is confusing. However, this lack of verticality is limiting in more ways than simply decreasing the play area. On the following play, the Panthers run what is effectively a four verticals play where all four receiver come-back to the ball upon passing the down marker.

As the Falcons know that they can give up receptions short of the yard marker, they are able to wait for the receivers at the heads of their routes and easily prevent the completion. What’s more, by running all the players to this level, the Falcons can drop all defenders to this point, thereby narrowing the windows Newton has to make his throws. The single underneath defender is then able to read Newton to either come down to McCaffrey if he drops the ball off or to help up the field, if necessary.

![]()

![]()

More importantly, as all the routes are run vertically, the safety is able to help on both central routes over the top, allowing the inside cover men to cheat on the underneath routes. This then forces Newton into a difficult outside throw, which falls incomplete; if Newton is able to make these throws on a consistent basis, he has a real shot at an MVP award, but they don’t make for a consistently effective offense. By using a similar concept to the 49ers play earlier, the Panthers could well have converted this third down. The diagram below shows what that might have looked like:

As with the 49ers play, the Bersin deep route forces the safety up the field and creates space on the inside of the drag route, as does the Olsen out route. This leaves a layers concept on the far side of the field with McCaffrey left one-on-one against the linebacker against the blitz. On first and second down, Newton would simply look to take advantage of that matchup; but with the long third down, Newton would read the layers concept, with the read being whether the linebacker comes down to the Funchess drag or not.

As mentioned earlier, a major advantage with many of these concepts is that they don’t require anything special from any of the receivers. Against man coverage, some receivers will be required to separate on routes such as slants and posts but against zone, the concept of ‘being open’ is almost entirely a question of spacing. The final advantage of using spacing in this way to create open receivers over the middle comes against the blitz. Especially against spread formations, the vast majority of blitzes are going to involve the inside linebackers. This, in turn, leaves the middle of the field open, allowing for easy completions to in-breaking routes. The following play from the Patriots win against the Jets is a prime example of this:

The current Panthers’ offensive system does an excellent job of dominating teams when Cam Newton plays at his MVP-best, what is fails to do it take the burden off both he and the receivers when he is not. By adjusting the Panthers’ system even slightly to give Newton more consistently completable reads, Shula would be able to eliminate some of the inconsistency which has plagued them throughout Newton’s tenure. Crucially, what with much of the Panthers’ receiving corps watching Sunday’s game from their sofas, these alterations scheme receivers open, rather than relying on their skills to do so. Either that, or the Panthers have to rely on Newton being asked to make throws like the following in order to keep them in games:

Being competent to the short middle of the field is important in every game, but against the Saints this week it will be vital, not just because of the Panthers depleted wide receiver personnel needing scheme help to get open, but because of where the Saints have been vulnerable all year when the quarterback drops back to pass.

| Type | Completions | Attempts | Comp % | Yards | Avg | % of plays |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHORT LEFT | 113 | 187 | 60.43% | 1084 | 5.80 | 31.38% |

| SHORT RIGHT | 112 | 184 | 60.87% | 1032 | 5.61 | 30.87% |

| SHORT MIDDLE | 76 | 107 | 71.03% | 845 | 7.90 | 17.95% |

| DEEP RIGHT | 20 | 57 | 35.09% | 595 | 10.44 | 9.56% |

| DEEP LEFT | 17 | 47 | 36.17% | 574 | 12.21 | 7.89% |

| DEEP MIDDLE | 4 | 14 | 28.57% | 126 | 9.00 | 2.35% |